“There arose a king… who knew not Joseph [or his family].” Exodus 1

I

It had happened so many times before. Circumstances had arisen that compelled a father to take unfathomable risks to protect his family. In reference to some, it would innocently be called “migration,” “pilgrimage,” “fleeing persecution,” or even “entrepreneurship”. In reference to others, it was villainized as “illegal immigration,” “border jumping,” “evading the cops,” “breaking the law.” It all depended who was in charge at the time.

The risk was that there was no path to citizenship for them in either place, the land from which they came or the land to which they were running. No Pax Romana passport to protect them. They were an occupied people, the disinherited, Palestinians without a recognized state, and once they crossed the border into Egypt from their native lands, their future would be deeply uncertain.

The risk was that there was no path to citizenship for them in either place, the land from which they came or the land to which they were running. No Pax Romana passport to protect them. They were an occupied people, the disinherited, Palestinians without a recognized state, and once they crossed the border into Egypt from their native lands, their future would be deeply uncertain.

Of course, Egypt was Rome too. However, the local powers were different. Herod had no jurisdiction there. Still, Aegyptus (Roman Egypt) presented its own sets of challenges, its own dangers. Joseph had to risk it though, for his children. The message had been clear: baby Jesus’ |hay-SOOS-sez| life was in danger. And that put the entire family in danger too.

They didn’t have time to go through the proper channels. They had to escape in the middle of the night. All they could hope is that their visiting Persian benefactors, the Magi from the Far East, would keep their word and not return to Herod to tell him where the the baby was. Maybe that would give the family enough time to get away.

II

Today marked seven years since their exile began. Jesus |hay-SOOS| had just turned nine. Tonight they would celebrate, but first Jesus and his brothers had to go register again.

It always felt weird to him to have to reenact the circumstances of his birth year after year. Of course, he didn’t remember anything about that day himself, but his mother and father had been telling him the story of it for as long as he could remember. The particulars were a little different in the annual reenactment, but some of the parallels were uncanny. A law passed that they would have to be counted. People trying to make home in a place that would not welcome them. The benign neglect or indifference of many. The shared struggle of others. The palpable hostility of some. Being forced to pay “taxes”. Only now there were no messengers from God bearing witness with songs of peace and goodwill, unless you wanted to count the fact that his parents always threw a party that day to mark it as something other than a day for the state to remind them that their lives were not their own.

Jesus went with his siblings to meet their obligation. The kids always had to go alone. Their parents could have been deported on sight. Though he felt much too old to do so under normal circumstances, Jesus clung to his oldest brother’s hand as they neared the door. Iago |e-YAH-go| squeezed his hand back reassuringly.

Jesus went with his siblings to meet their obligation. The kids always had to go alone. Their parents could have been deported on sight. Though he felt much too old to do so under normal circumstances, Jesus clung to his oldest brother’s hand as they neared the door. Iago |e-YAH-go| squeezed his hand back reassuringly.

The lady who took their information was nice enough, as if that made a difference. Perhaps it did, but it didn’t lessen the injustice of the situation any. There were lots of Jews there. Lots of other people too, anyone who wasn’t a Roman, Greek, or Egyptian citizen (in descending order of status). One by one their vitals were taken: name, age, weight, height, hair color, eye color, distinguishing marks, ethnicity, place of origin, current address. Records were updated. Then the point of it all—the fee.

“Why must the poor and working people pay so much so often when they can least afford it? Why are we treated as criminals, when we are not?” Jesus asked his older brother as they headed home.

“I’m not sure,” Iago replied. “I guess that’s what happens when someone else makes the rules.”

“When I grow up, I’m gonna change that, since I’m supposed to be king and all,” Jesus prophesied mischievously.

Iago laughed. “I bet you will. We just have to convince Herod to give up the thrown.”

Jesus smiled back and began to skip out ahead of his siblings. That was one of the parts of the story he wasn’t sure how to make sense of. His parents had told him the reason they had to leave Bethlehem was because Herod, Tetrarch of Galilee, saw him as a threat the way Pharaoh of old had seen baby Moses so many years ago. In fact, irony of ironies, this King Herod, himself a Jew, felt so threatened by Jesus’ possible claim to his throne that he stole a play out of the ancient Pharaoh’s playbook and set about trying to kill every male child under the age of two in Bethlehem, thus necessitating Jesus’ family’s escape to the land of Pharaohs. It’s so amazing how easily “good guys” and “bad guys” switch places.

But they weren’t a royal family, Jesus continued to wonder. Joseph and Mary were peasants. Sure, they were of the line of David, Israel’s greatest king, but “Nowadays everybody is,” his siblings had told him sarcastically. Plus, with Rome in charge back home as well, with its emperor and senate and elites and varying levels of citizenry, ancient myths of the lines of succession for an occupied people didn’t matter. Neither did promises of a Messiah, a deliverer like Moses, who would once again set his people free. “All that matters is one’s relationship to Rome,” he had heard Iago say. Or is it? What if Rome didn’t really matter much—at least not in the way they thought? What if Herod knew it? What if that was the source of his insecurity?

III

It shouldn’t come as a surprise. Ancient Egypt had been the land of both enslavement and opportunity for children of Israel (Jews) on more than one occasion. But time and time again, for fear of how their mounting numbers and influence might translate into political power, like clockwork, the powerful of Egypt eventually turned against them.

This time it wasn’t outright enslavement and “kill the firstborn males.” (That hadn’t worked out so well that one time.) This time it was more subtle. Jews could keep their own communities, villages and enclaves. But they would have to follow a set of rules not made for them or by them.

The rules here would be a variation on the place they had left. So many had arrived as children. They were still young and strong. They must register, so we can track them. In fact, make them have to go down to the detention facility to re-up every six months. Educate, colonize, condition their minds in their youth to think like us. Then plunder their young adult immigrant bodies for labor; welcome them to die in our wars with the promise of upward mobility; let them fill menial, agricultural, and entry level positions; “tax” them at a higher rate than those who do little, if anything, to create actual wealth—all the while withholding from them the chance to even file for citizenship for another 15 years, thus missing the right to vote for at least 3 elections, though of voting age. And, ultimately, reserve the right to reject their applications for citizenship just as they come of age (mid-thirties) to demand higher wages. Give them the false choice between this deferred action arrangement and immediate imprisonment for deportation. And for peak irony, call it The SUCCEED Act.

Though those might not have been the particular parameters of the way inequity manifested that time (as it is in America 2017), we can bet it was something. So Jesus |hay-SOOS| and his siblings had to grow up going through whatever humiliations were a part of being second class denizens in Aegyptus, the wealthiest province of the Roman empire outside Italia. They were branded “strangers in a strange land,” yet again, though at that point, it was the only country Jesus knew. If given any kind of legal status, they would have had to report to be counted and taxed whenever and wherever the law said to. They would have been singled out by their status. They would have been looked down upon. They would have been denied access to the rights of full citizenship. As those on the bottom of the social order, they would have been exploited multiple times over for their labor. Out of a Palestinian frying pan, into an Egyptian fire.

Though those might not have been the particular parameters of the way inequity manifested that time (as it is in America 2017), we can bet it was something. So Jesus |hay-SOOS| and his siblings had to grow up going through whatever humiliations were a part of being second class denizens in Aegyptus, the wealthiest province of the Roman empire outside Italia. They were branded “strangers in a strange land,” yet again, though at that point, it was the only country Jesus knew. If given any kind of legal status, they would have had to report to be counted and taxed whenever and wherever the law said to. They would have been singled out by their status. They would have been looked down upon. They would have been denied access to the rights of full citizenship. As those on the bottom of the social order, they would have been exploited multiple times over for their labor. Out of a Palestinian frying pan, into an Egyptian fire.

And if denied or at some point stripped of legal status—it had happened before—then they would live in fear of being deported or, worse, separated from one another, torn asunder like so much trash. They would only be able to be paid under the table. That meant Joseph and his sons’ skill as carpenters and Mary’s skill as a weaver and seamstress would, more often than not, be undervalued. They would have no protections. They would likely be cheated regularly and threatened should they try to press the issue. Yes, it was nice that Aegyptus had public education and emergency medical care. However, one could never be too careful. Interfacing with any government agent was a potential threat to one’s well-being. That meant when the Nile flooded every year beyond the capacity of the levies and aqueducts to manage, as one who was undocumented and relegated to low-lying areas, they might lose everything and have to start over from scratch. Of course, the community of those who were in this predicament would help one another, but it would never be easy.

Whatever the terms of their situation, the inequity of it would be apparent. Social stratification was Rome’s thing. As long as they rendered themselves virtually invisible, non-threats to the social order, they would be tolerated, convenient pawns in the hands and mouths of the powerful to shame overtaxed “working class” Egyptians into not complaining.

The way the story has been handed down to us, it’s easier to imagine that, having fled for their lives, Joseph and Mary’s family lived comfortably secure in this land that was not their own. But with all the history between Egyptians and Jews—with the realities of Roman military domination, exploitation of labor, and infatuation with taxation—that wouldn’t have been very likely.

IV

When the siblings got home, their parents were busy preparing for the night’s festivities. It would be a potluck. “With everyone bringing their favorite dish, there will be plenty,” Mary assured them.

And there was. Guests laughed and danced and ate late into the night. They forgot for the moment the difficulties of occupation. The most delicious smells filled the air. Neighbors took turns sitting in with the band. Kids ran around oblivious to the cautions of elders. Elders shook their heads as they spoke of times past. It was joyous.

And there was. Guests laughed and danced and ate late into the night. They forgot for the moment the difficulties of occupation. The most delicious smells filled the air. Neighbors took turns sitting in with the band. Kids ran around oblivious to the cautions of elders. Elders shook their heads as they spoke of times past. It was joyous.

Unexpectedly, the tenor of the festivities began to change. Like dye dropped into a bowl of water slowly winding its way throughout, the question began to spread, “Where’s Joseph? Has anyone seen José and Maria?”

A messenger had arrived with urgent news. He came yelling up the street, “Please, tell me where Joseph and Mary are!”

“I think I saw them over there,” came one reply.

“They must have gone back to the house,” came another.

He found them in the street in front of their house in the midst of a crowd laughing at one of Joseph’s outlandish stories of the circumstances surrounding Jesus’ |hay-SOOS-sez| birth. It was funny now, not so much then.

“He has a message for José,” someone at the back whispered. Guests hurried to clear the way.

Someone tapped the shoulders of the musicians and the song they sang came to a calamitous halt. Jesus looked up from the game of dreidel he was playing with his friends.

“Shh! Listen.”

Staring into José’s eyes, Angel |AHN-hel|, the messenger, catching his breath, panted, “H… Heh… Herod is dead!”

Check out the PREQUEL: “Occupy Bethlehem”

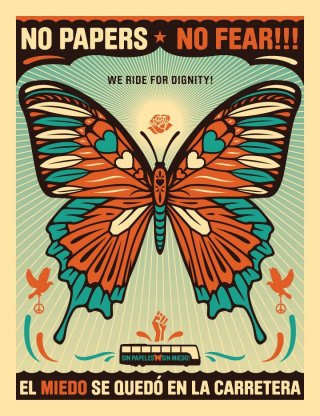

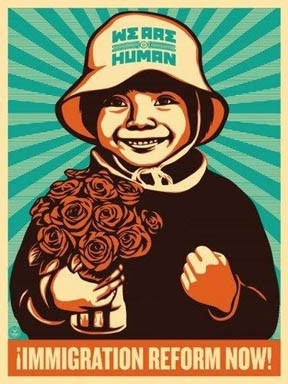

Photos courtesy of Mijente and in celebration of the immigration justice work being done to protect the vulnerable, mobilize the marginalized, and advance our collective humanity.

Story inspired by “Facing Christmas ~ Week 2 ~ Counted,” produced by Hannah Bonner